Society

The world's oceans are going through their own brand of inflation, with a higher needle on the thermometer becoming the norm throughout the year, year after year. The human need for consumption often fuels the desire for better days, and our sooty relations with carbon emissions is no exception. Cutting emissions alone may not bring the scale of relief required, but across continents, monumental carbon removal plants are on the rise with a shift to the sustainable. Just how much of it is greenwashing, though? And can this year's Chemistry Nobel laureates really change how humanity traps its carbon?

Fifty Shades of Carbon

Colour coding carbon isn't just for chemistry class. In industry, carbon colors signal how carbon is produced and processed. Black carbon refers to soot from incomplete fossil combustion; it worsens air quality and health and grey carbon comes from the more renowned energy producing torrid fossil fuel based operations. Blue carbon marks the capture and sequestration of carbon by oceanic and coastal ecosystems, like mangroves, seagrasses, and tidal marshes. Green carbon highlights carbon stored in terrestrial forests and plants. Turquoise carbon is the new kid on the block: produced when methane is split into hydrogen and solid carbon, rather than CO₂, for clean hydrogen production using methane pyrolysis.

Globally, fossil fuel processes remain responsible for about 90% of annual anthropogenic emissions, with grey carbon leading the charge. Blue and green carbon landscapes offer natural offset potential, tidal mangroves, for example, can trap over 4.5 gigatons CO₂-equivalent per year, according to a 2022 UN report.

In Bangladesh, over 85% of total CO₂ emissions derive from natural gas and coal based energy, with rapid urban growth in the capital fueling demand. One of the world's largest tidal mangrove forests, the Sundarbans, is a linchpin for the nation's blue carbon strategies. The World Bank estimates improved blue-green carbon management could help Bangladesh offset as much as 20 million metric tons of CO₂ by 2030. Recent local pilot programs have focused on expanding sustainable aquaculture and restoring diminished mangrove cover in the south-central Sundarbans.

Boston Consulting Group's latest reports paint a nuanced portrait of the evolving industry. Carbon storage capacity worldwide is estimated at well over 1 GTon/year, but actual deployment is a fraction of what's needed to hit net-zero targets. BCG figures highlight maritime shipping as a crucial, under-addressed sector, responsible for about 3% of total global emissions. Maritime decarbonization strategies like methanol, synthetic carbon or ammonia fuels are gaining traction, particularly in South Asia's major shipping lanes.

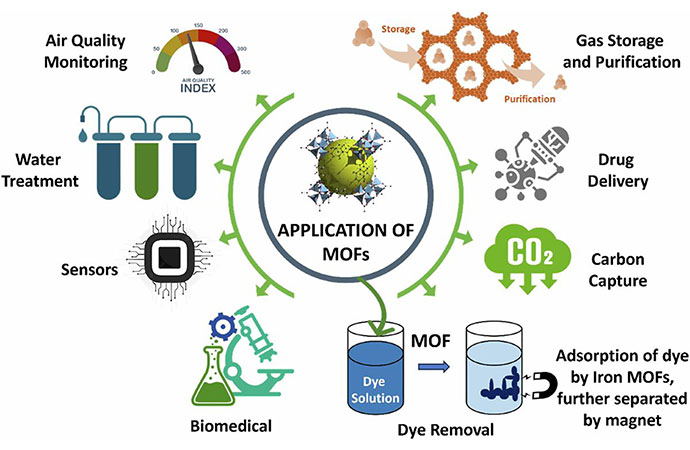

But successful carbon capture demands national incentives (like expanded 45Q tax credits), efficient permitting for pipelines, storage and reuse, strict regulations for geological sequestration, and support for foreign R and D demonstration projects. Frameworks such as the EU's Carbon Border Adjustment and Disclosure mandates standardizing emissions-accounting. On the ground, next-gen tech like Metal Organic Frameworks, Direct Air-Capture hubs and nature based solutions must align with transparent policy engagement for any scaled deployment.

Soot and Solutions

The oceans are responsible for storing most of the world's captured carbon. Now, on Singapore's coast, Equatic (series A funded startup) is scaling an ocean based carbon removal plant.

Equatic's process works like this: first, it pumps sea water into an electrolyser, converting the seawater to hydrogen, oxygen, an acid stream and an alkaline slurry of calcium and magnesium based materials.

The alkaline slurry is then exposed to air, pulling and trapping CO2, after which it's discharged into the sea as dissolved bicarbonate and solid mineral carbonates, thus immobilised for tens of thousands of years. "Unless that carbonate is heated to a high temperature of around 900C, that CO2 will not be re-released." says Sifang Chen, a science advisor at Carbon180, a Washington-based non-profit advocating for carbon removal solutions.

According to CNN, the facility is expected to remove 3,650 metric tons of CO₂ annually once fully operational, the equivalent of taking several hundred cars off the road. Revenue comes not only from carbon credits but also from producing green hydrogen as a byproduct. Still, ocean capture remains controversial: critics warn of marine biome adversities, and a distraction from fossil fuel reductions.

A thousand miles away, on the volcanic plains of Iceland, Swiss company Climeworks has opened the world's largest direct air capture or DAC facility, Mammoth. Built beside geothermal plants, the DAC site filters ambient air through massive collectors containing chemical sorbents that strip out CO₂. Partnering with local firm Carbfix, Climeworks then injects the carbon deep underground, where it reacts with basalt to become solid stone over time, locking carbon away for millennia.

At peak, Mammoth is expected to capture 36,000 tons of CO₂ annually. Climeworks anticipates falling prices to $300 per ton (currently around $1000) by 2030 and dreams of reaching $100 per ton by 2050, reports from Yale indicate.

Worldwide, the CCUS (carbon capture, utilization, and storage) market is projected to surpass $10.3 billion by 2032, expanding at more than 13% compound annual growth. North America currently leads, with Asia-Pacific and Europe also prowling.

Nobel 'Frameworks' and Novel Frontiers

Carbon capture technology celebrated its own Nobel moment, with this year's chemistry laureate Omar Yaghi (UC Berkeley). Yaghi, born in Amman, Jordan, in 1965 to Palestinian refugees, shared the honour with Susumu Kitagawa and Richard Robson for their work developing metal-organic frameworks.

"I grew up in a very humble home, we were a dozen of us in one room, sharing it with the cattle that we used to raise. I was born in a family of refugees, and my parents could barely read or write. My father finished sixth grade and my mother couldn't read or write. It's quite a journey. Science allows you to do it. Science is the greatest equalising force in the world..." Yaghi noted to the Nobel committee.

MOFs and their crystalline, modular structure feature enormous internal surface area and tunable pores that can selectively trap CO₂ out of gas streams. Companies like BASF are deploying MOF-based capture systems on flue gas. The Nobel committee lauded the trio for creating "materials that connect molecular design to global sustainability".

In 1999, Yaghi, then at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, revealed the work that would cement the status of metal-organic frameworks. Instead of linking up ions, Yaghi and his team used more complex metal clusters as the hubs. Their iconic material, known as MOF-5, was a cubic lattice with huge cavities. A couple grams of the material have the surface area of a football field.

Research groups are exploring how MOFs could be deployed within ocean-based removal plants, using their high selectivity and surface area to 'filter' carbon from massive seawater flows. Beyond carbon capture, MOFs also catalyze reactions, harvest water from desert air, and help purify hydrogen for H-cell vehicles. The materials could also be used to sequester toxic wastes, or simply to identify when they are present.

The advent of AI is also heavily leveraged to design next-gen MOFs, predicting optimal structures for varied industrial gases and automating synthesis. Some industry players envision DAC farms adapting in real-time based on atmospheric (black carbon) data, maximizing removal while minimizing energy costs.

Integrating DAC and MOF based technologies into green hydrogen production could also neutralize 'grey' emissions from methane reforming and help foster a fully circular hydrogen economy. Funding remains a patchwork, upwards of $20 billion in public and private investment are in the pipeline for CCUS globally.

In a world built on carbon, capturing, storing and selling it, or even turning it into building blocks, may seem like closing the barn door after the carbon horse has bolted. But as this year's Nobel laureates demonstrate, it's the right chemical reaction that can tip the scales.

Shoumik Zubyer is an Associate Researcher at the Atmospheric and Environmental Chemistry Lab, Atomic Energy Centre, BAEC and a science writer.

Leave a Comment

Recent Posts

Another stress-test for the wo ...

And just like that, the world economy has been thrown into turmoil onc ...

Turkish President Recep Tayyip ...

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan offered to mediate for a new ce ...

Bangladesh flags economic risks of prolonged Middle ..

Bangladesh seeks enhanced cooperation with Argentina

US trade deal discussed with BNP, Jamaat before sign ..

Road Transport and Bridges, Shipping, and Railways M ..