Featured 2

Innovative Genomics Institute

Contemporary gene editing has transformed from an obscure bacterial defense mechanism into medicine's most auspicious genetic scalpel. With a Nobel Prize to the pioneers and a promise to reshape everything from agriculture to human longevity, regulatory approvals accelerate as we stand poised to redefine hereditary determinism.

A Crisp Introduction

CRISPR, (Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats), represents a prized possession of the microbial realm - an antiviral system. Emerging from bacteria's ancient immune defense suite, where DNA sequences store "memories" of viral invaders alongside scissor (Cas) proteins that slice up foreign genetic material.

A seminal breakthrough came in 2012 when biochemists Emmanuelle Charpentier (Director, Max Planck Institute for Infection Biology, Berlin) and Jennifer Doudna (Chancellor's Chair, Biomedical Health Sciences, University of California, Berkeley) first demonstrated that CRISPR Cas9 could be programmed to cut any DNA sequence. Their collaboration, sparked at a scientific meeting in 2011, united Charpentier's discovery of tracrRNA (a key guide molecule in bacterial immune response), with Doudna's expertise in RNA structure.

Awarded the 2020 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for their work, this had made them the first all-female team to share a science Nobel. The committee praised their development of "one of gene technology's sharpest tools," noting that CRISPR had already "benefited humankind greatly" within just eight years of discovery.

The Programmed Scalpel

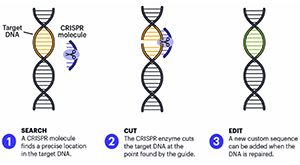

At its molecular core, CRISPR functions like a GPS-guided surgical machine. The system relies on two key components - a guide RNA that serves as the targeting system, and a Cas protein that acts as the cutting enzyme. The guide RNA contains a 20 nucleotide sequence that matches the target DNA sequence, much like a molecular ZIP code directing the Cas9 protein to the exact gene address requiring modification.

Cells respond to this cut through natural repair mechanisms. When provided with a DNA template, the directed repair can incorporate specific changes according to the required homology. This repair process transforms a simple cut into precise modifications, whether correcting disease causing mutations or inserting entirely new instructions.

The elegance lies in the system's programmability. Researchers need only design new guide molecules to redirect the scissors to different genomic targets, which is what makes CRISPR exponentially more versatile than any alternative.

Since the Nobel recognition, CRISPR has evolved far beyond its original Cas9 incarnation. The new renditions, from Cas12 to Cas14, are the most promising new frontier in the field of synthetic biology. The technology has democratized genome editing, what once required specialized facilities and months of work is now a matter of mere days.

Bleeding Edge Medicine

A watershed moment for clinical reality of this tool came in December 2023 when the FDA approved Casgevy, the first CRISPR based therapy for sickle cell disease and beta thalassemia. This kickstarted the bleeding edge developments that are to follow.

The therapeutic pipeline has exploded with a historic milestone in 2025 by treating an infant with a metabolic disease using personalized CRISPR therapy at the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia. An infant, KJ, was born with a rare metabolic disease (severe CPS1 deficiency). After spending the first several months of his life in the hospital, on a very restrictive diet, KJ received the first dose of his bespoke therapy at seven months of age. "While the child will need to be monitored carefully for the rest of his life, our initial findings are quite promising," said PhD researchers from UPenn.

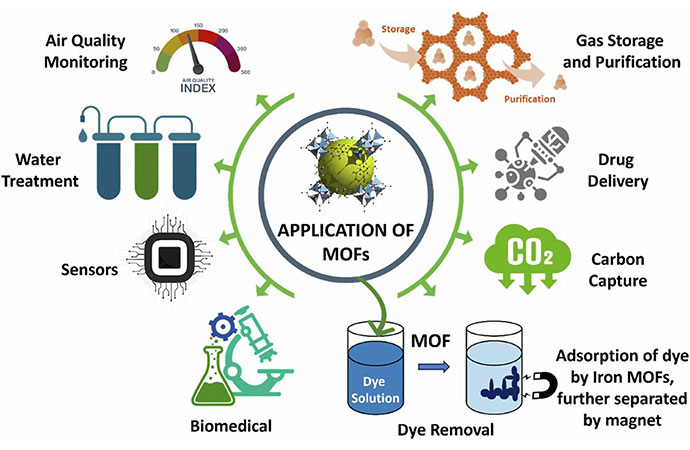

Swedish scientists have engineered "hypoimmune" pancreatic cells using CRISPR-Cas12b, stripping away rejection markers and boosting a "don't-eat-me" signal so they can be transplanted without lifelong immunosuppression. While scientists from Washington University fixed the WFS1 gene in a patient's stem cells and turned them into insulin producing beta cells that cured diabetic mice for six months. Industry backed trials now possess liver-targeted CRISPR technology that cuts LDL cholesterol by nearly 60 percent, tangling diabetes and its heart risks in one sweet sweep.

Cancer immunotherapy has emerged as CRISPR's most enthralling beacon. Next-generation CAR-T cell therapies now incorporate multiple gene edits to enhance anti-tumor manifests. Clinical trials, such as reports from Caribou Biosciences show that 15 of 16 patients with aggressive lymphomas responded to CRISPR-enhanced CAR-T treatment, with seven achieving complete remissions lasting six months or longer, exceeding conventional cancer therapies while potentially offering more durable responses, at competitive costs.

Environmental applications showcase this tool's true versatility. Researchers at UC San Diego and Johns Hopkins University have engineered Anopheles stephensi mosquitoes - Asia's primary malaria vector. Using what is known as gene-drives, the mosquitoes retained normal fitness and reproduction capabilities while losing their ability to transmit malaria parasites. These modifications could theoretically, easily spread through wild populations.

Researchers even use gene circuits built with CRISPR components to force microbes into producing pharmaceuticals, biofuels, or industrial chemicals. Space biology applications are also emerging, with scientists developing engineered archaea for terraforming applications within bioreactor setups. Such bio-systems might produce oxygen, food, or even building materials on Mars using resources in-situ.

Eco-restoration applications push CRISPR into uncharted territory. Some experts are modifying coral species with heat tolerance to combat bleaching events caused by rising ocean temperatures. Others offer solutions for invasive species management, citing a biocontrol "Silver Bullet" of sorts. However, these applications of gene-drives raise profound ecological questions about unintended consequences and irreversibility, as well as upending ethical notions.

So far, the most controversial are de-extinction efforts such as the efforts of resurrecting extinct species. Colossal Biosciences engineered "woolly mice" by editing nine genes simultaneously, producing reddish gold fur and dense coats three times longer than normal, traits mimicking extinct woolly mammoths. All 38 surviving mouse pups from nearly 250 embryos expressed mammoth-like features and cold adapted metabolism. The agenda remains sturdy for the company's 2028 mammoth de-extinction project timeline.

The environmental stakes extend beyond individual applications. Gene drives could theoretically spread modified traits through entire wild populations within generations. Critics warn of potential ecological disruptions, including altered predator and prey relationships, biodiversity loss, and potential but very likely, population crashes.

The Designer Baby Dilemma

Perhaps no CRISPR application generates more debate than human embryo editing. Regulatory frameworks are evolving to address CRISPR's rapid advancement as the FDA has established comprehensive guidelines for CRISPR therapeutics, requiring long-term follow up studies lasting up to 15 years.

In 2018, a Chinese scientist secretly used CRISPR to disable the CCR5 gene in twin girls' embryos, aiming for HIV resistance, a move that sparked global outrage over ethics, off-target genetic risks.

Even more recently, a U.K. team gained approval to repair a fatal MYH7 heart defect mutation in a single infant's embryo, conducting ex vivo editing and rigorous genetic screening under strict oversight. Initial health checks are promising, but long-term monitoring is pivotal for developing a germline editing policy.

Current scientific consensus supports therapeutic applications while maintaining strict boundaries against enhancement editing. The distinction between treating disease and improving human traits remains contentious, with critics warning that genetic enhancement could create new forms of inequality based on "genetic privilege".

The future may well be gene-screened before it arrives, whether that future is a cure all or a descent into genetically stratified castes depends largely on choices made today by scientists, regulators, and society at large. As the 1997 film Gattaca quipped, "There's no gene for the human spirit," yet we flirt with a world where resumes may list DNA scores for competency analysis.

And what happens if we replace human potential with genetic prophecy? The question may dither to temptations of editing our very humanity out of existence.

Shoumik Zubyer is an Associate Researcher at the Atmospheric and Environmental Chemistry Lab, Atomic Energy Centre, BAEC and a science writer.

Leave a Comment

Recent Posts

Another stress-test for the wo ...

And just like that, the world economy has been thrown into turmoil onc ...

Turkish President Recep Tayyip ...

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan offered to mediate for a new ce ...

Bangladesh flags economic risks of prolonged Middle ..

Bangladesh seeks enhanced cooperation with Argentina

US trade deal discussed with BNP, Jamaat before sign ..

Road Transport and Bridges, Shipping, and Railways M ..