Global

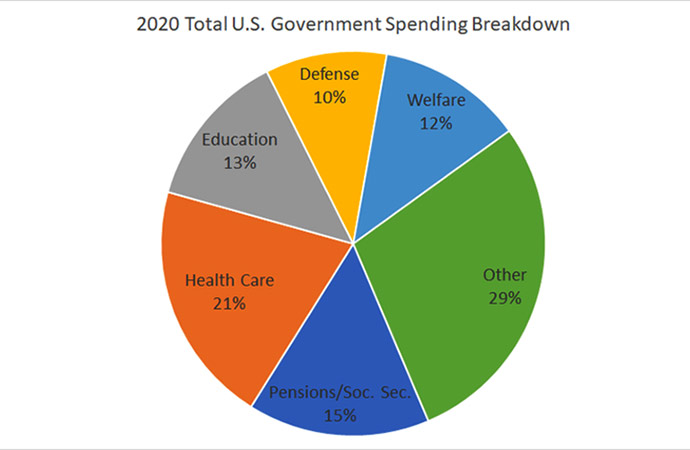

A breakdown of US government spending in 2020 | wikimedia commons / Public Domain

The past 50 years of Western economics are rooted in imperial exploitation. But if the US’s military can be beaten, it can’t rule global markets

The neoliberal era, which arrived as the US lost the Vietnam war, has ended with America losing the war in Afghanistan. And the war on terror. And the war on drugs.

Images on Twitter timelines, TV screens and in group chats tell a gruesome story for those who face slaughter and subjugation by the Taliban. Women, Shia people and anyone who collaborated with US and UK forces or with the now-essentially defeated regime face a grim future, as the "hooligans of the absolute", as the political thinker Tom Nairn dubbed them, take control of the country once more.

I can't help but think of the Afghans I met in a refugee camp in Belgrade in 2015. One man had been shot in the leg while serving in the national army alongside British troops. He was flown to a hospital in Cardiff, where he spent a year recovering. But he was denied asylum, and sent back to Afghanistan. Knowing Taliban forces would kill him and his family, he had walked all the way to Europe on his gammy leg, with his sister and her children.

Were they turned back at the EU border? Have they been killed? I tried to stay in touch on Facebook, but I've no idea what happened to them.

I can't help but think of the 32,000 Afghan asylum seekers the UK has turned away since 2001, as openDemocracy revealed yesterday. Did Britain's deportation flights deliver them to firing squads?

I can't help but think of my grandmother, who was in her late 80s when the NATO invasion began in 2001. "Didn't we learn our lesson in the second Afghan war?" she asked the teenage me, referring to the British invasion in 1878, only a generation before she was born.

I can't help but think of the accounts of the first Anglo-Afghan war, in 1839, when Britain invaded, was kicked out of, and then reinvaded the country as 'revenge' - murdering, raping and starving whole villages as they went, so they could turn this human society into a buffer zone for their Indian colony. This isn't a 20-year history, it's a 200-year history.

I can't help but think about the war on drugs. If, instead of criminalising heroin and driving its central Asian growers into the pockets of the Taliban, we had legalised and regulated it, where would we be?

I can't help but imagine why so many teenage boys and young men who have known nothing but NATO occupation are so desperate to overthrow the government that they will align with foreign fighters and slaughter their neighbours.

And I can't help but wonder at the failure of Britain's national press to ask these questions. Twenty years of war, twenty years of supposed nation-building by what started out as the most powerful alliance in human history has been swept aside in a matter of days.

The neoliberal era is over. And as we see in Kabul today, what comes next isn't inevitably better.

Is neoliberalism really over?

There has been a bit of debate of late about whether neoliberalism is dying, or changing. Events such as this year's G7 agreeing, in theory at least, to a global minimum corporation tax, encouraged the economic historian Adam Tooze to say that the elite consensus around neoliberalism as an idea is gone.

Just as significantly, as openDemocracy co-founder Anthony Barnett has pointed out, the height of neoliberalism was defined by a denial in elite circles that such a thing existed. "You might as well debate whether autumn follows summer," Tony Blair argued in 2005, against those who wished to discuss the globalisation of Western markets.

This wasn't an ideology, they'd say, just logic, just the way things are, just reality. These days, even the Financial Times is starting to question whether neoliberalism works - yes, using that word - and the arch think tanks of the ideology have returned to using the term. Their idea isn't common sense anymore - it needs defending.

Economics journalist Grace Blakeley thinks neoliberalism is alive and well, though. Writing in Tribune in May, she argued: "The neoliberal state is not a small state, it is a state designed to meet the interests of capital". COVID bail-outs, she concludes, don't spell the end of neoliberalism. "States are spending more money because big business and big finance needs to be bailed out - again."

The following month, historian Quinn Slobodian quite rightly pointed out the ideological connections between the new, nationalist Right - the Trumps, Bolsonaros and Brexiters - and the neoliberal Right. The forefathers of neoliberalism were much more racist than we're usually told, and the nativist, new Right is much more closely aligned to big money than it likes to admit.

If Donald Trump's former chief adviser, Steve Bannon, glorifies Hayek - and he does - isn't he a neoliberal too?

Both James Meadway, writing for Novara, and openDemocracy's economics editor, Laurie Macfarlane, argue, however, that a shift in the international order points to the replacement of neoliberalism by a system of authoritarian capitalism, typified by the rise of China, but also by Trump's breaking of neoliberal trade agreements.

And we can understand the US retreat and defeat in Afghanistan only in this context.

What was neoliberalism?

Usually, neoliberalism is described as an ideology - the belief that the state should be rolled back and the market allowed to roam free - developed in the famous think tanks and university economics departments of Anglo-America.

I don't think that's the best way to look at it. Opinion polls in countries around the world consistently show that neoliberal ideas such as privatisation, tax cuts for the wealthy and deregulation are deeply unpopular. And yet they have dominated for 40 years. Neoliberalism is an idea, but it wasn't powerful because of its success as an idea.

The academic William Davies has provided perhaps the most succinct definition, which frames neoliberalism as a sociological process: "the disenchantment of politics by economics". This gets to the heart of a lot of what went on - the shifting of decisions from the political sphere to the market: one person, one vote to one dollar - or pound or euro or yuan - one vote. Or perhaps a million dollars.

If the first half of the 20th century saw women and working-class people win the right to elect national governments, the final quarter saw those running those governments hand power elsewhere, to ensure that most people never really got near it.

But I prefer to see neoliberalism another way: as an historical and geographical process.

For centuries, the dominant form of capitalism was colonialism. People who had money realised that one very good way to make more of it was to pay for someone to go somewhere else, and plunder.

Double-entry bookkeeping, invented in medieval northern Italy, allowed businesses to monitor capital, credit, loans and investments. One early adopter was Christopher Columbus, who took a royal accountant on his notorious 1492 voyage.

Soon, Europeans became the world's experts in capital accumulation through colonial violence: hence the genocides of the Americas and Australasia, the East India Company's brutal conquest of South and South East Asia, the murderous Scramble for Africa and the Opium Wars, to give just a smattering of examples. Control of global markets helped produce the industrial revolution, which intensified the process.

European-Americans followed the example with zeal, genociding and conquering the 'wild' west - with the Dakotas, Washington, Idaho, Wyoming and Utah incorporated as states in the late-19th century, New Mexico and Arizona in 1912, and Hawaii and Alaska in 1959 - alongside the de-facto colonisation of much of the Pacific (the Philippines were a US colony from 1898-1946, Micronesia was under US administration from 1945 to 1986.)

This westward expansion of the American empire got into trouble when it hit the Asian mainland, and bumped into Chinese and Russian power - with the 1968 Tet offensive in Vietnam delivering not just military defeat, but also popular uprisings across the Western world.

Unable to reach into this terrain, but dominating much of the rest of the planet, Western capital had hit a boundary. After a brief flirtation with space travel, it was unsure where to go next. It was no longer simple for capital to colonise somewhere 'new'.

I tend to think of neoliberalism as the response of Western capital and its allied states - and led by US capital and the American state - to that boundary. It was an attempt to create a single global market with the US and, to some extent, western Europe, at its core. It's not a coincidence that it came immediately after the break-up of most of the British empire - in many ways, it was America's attempt to replace it.

US military defeat first in Iraq, and now in Afghanistan, marks the end of that era.

Consent to govern and humanisation

Two inventions, both in 1947, helped accelerate the shift away from traditional imperialism by ending the vast asymmetries in violence between colonised and coloniser. Unlike their predecessors, the AK-47 assault rifle and the Toyota Hilux could be fixed in the field when they broke down or jammed, and their widespread distribution provided cheap and accessible means for mass violence. The tools of war were democratised. The power of insurgents grew.

Just as significantly, communications technology had transformed too. The world became more connected than ever, and, as Anthony Barnett described last year, the uprisings of 1968 helped create a sense of global community.

The violent reality of empire had always been contested in the imperial centres. In May 1840, during the first Opium Wars, William Gladstone wrote in his diary that he lived "in dread of the judgments of God upon England for our national iniquity towards China". But the judicious distribution of plunder, patriotism and propaganda had allowed the system to secure sufficient consent to operate.

Just as the plunder had begun to dry up as imperial capital reached its geographical boundaries, so, too, the systems of propaganda started to break down. The significance of the Tet offensive wasn't just the military shift in fortunes. When North Vietnamese forces received the order to "crack the sky, shake the earth", they did just that, but not only in the way they imagined.

In the US, colour television had started to take off, colour photography was already dominating the front pages of the nation's magazines. While European empires had faced disasters in previous decades, their citizens sitting at home had never seen them so vividly.

But at the same time as America was losing the propaganda war in Vietnam, it was winning the secret war in Indonesia. Two months after the Tet offensive began, US-backed Suharto was sworn in as president of what was then the world's fifth most populous country. It took until 2017 for the scale of the CIA's involvement in murdering a million people to be officially confirmed.

Suharto used US-trained economists to force markets open to American capital, creating what Transparency International would later describe as "the most corrupt government in modern history". He remained in power until 1998.

Five years after Suharto's swearing-in, a similar model was used to depose Chile's elected president, Salvador Allende, in a flurry of bomber jets, replacing him with General Pinochet and a shock of US-trained economic advisers - students of the Chicago University professor, Milton Friedman. Pinochet's regime is often seen as the first experiment in neoliberalism.

As the writer and academic David Wearing has pointed out, an important feature of this system has been a willingness to ally with all kinds of brutal, fundamentalist and authoritarian regimes if they align with the interests of Western capital. As he says, you don't need to conduct a thought experiment to see how the British and US governments would treat the Taliban were they useful to them. You only need to look to the House of Saud.

In fact, in her seminal book 'The Shock Doctrine', writer and activist Naomi Klein shows that the myth that US capital advanced around the world hand in hand with democracy is a lie. Rather, she explains, it was through the exploitation of crises and administration of violence that countries were forced into the globalised neoliberal economy.

Another feature of this system is that it responded to the lack of new territory to conquer by focussing on extracting wealth from the Western states it had previously relied upon as its key allies in conquest, through the privatisations that became one of its defining properties.

While reductions in government spending were sometimes part of the rhetorical programme, they were less frequently a feature of reality. US government spending has remained roughly the same throughout the neoliberal era. The real process that's taken place in Washington has been a rapid growth in military spending, making up for a fall in other funding.

While the US tried to expand its control, European powers, bankrupted by WWII, faced in their empires resistance movements increasingly armed with those AK-47s and Hiluxes and with superior local knowledge. The Europeans feared that ongoing attempts to govern their colonies would lead them to full alignment with the USSR and so retreated from them.

One consequence of these processes was the formation of the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) in 1960. Where British companies had previously effectively stolen oil from beneath the Middle East, now, domestic autocrats wanted their share. And in 1973, as the Yom Kippur war raged, they revved their engines, and quadrupled the price of oil. Along with the financial turmoil produced by the defeat in Vietnam, these events produced the economic crisis of the 1970s.

Richard Nixon, advised by those Anglo-American economists and think tanks, abandoned the post-war agreements that had held together the social democratic consensus across the West since World War Two, plunged the dollar off the gold standard, and ushered in the new consensus of marketisation, known to its founders as the neoliberal system.

In the next decade, the Soviet Union would also discover how technology had democratised violence as it met the US-armed Mujahideen in Afghanistan, who ultimately contributed to its downfall. But that's another story.

The mechanisms for trying to control these former colonies - and for ensuring the continued transfer of wealth from South to North - continued. The World Bank and IMF imposed conditions on loans, known as structural adjustment programmes, which did nothing to alleviate poverty and everything to ensure Western capital got to eat from the table first. Complex corporate-ownership structures were developed. Undercover operations continued, and wars were still waged - particularly against regimes that controlled large supplies of oil.

But, unlike the days of empire, when the control of colonies by colonisers was clear, even if the mission was sometimes spun as Christian and civilising, the process was always made opaque. The impoverishment of the already poor was somehow always justified as being for their own good, or as part of the natural order of things. As global connectedness expanded, it was harder to murder, torture and plunder in other countries without facing a backlash at home: compare, for example, the limited reaction against Britain's mass-torturing of Mau Mau prisoners in the 1950s and 1960s with the backlash against the human rights abuses committed in the Iraqi prison, Abu Ghraib, by the US in the early 2000s.

The main difference between the UK's success in the Malayan 'emergency' (1948-1960) and the US's defeat in Vietnam was, arguably, that the UK could get away with using concentration camps.

As the US embraced its role as the world's primary imperial power, it faced the significant challenge of managing a domestic population more connected to the rest of the world than that of any previous imperial centre. And so it developed a whole thicket of mechanisms for obscuring the processes of plunder that were going on: from shifting control to corporations to handing power to transnational institutions to vast expansions in debt, both internationally and domestically.

And one of those mechanisms was the propaganda of liberal interventionism, the idea that Western military intervention was being done for the good of the citizens of wherever was being intervened in.

Of course, you can perfectly reasonably argue that some such interventions were in fact good for the residents of the countries that were bombed, that they were better off without whichever regime was deposed. That's a conversation for another day. But it's hard to argue that humanitarian ideals were the primary motivations for the various bombings at the height of neoliberalism: brutal regimes weren't just tolerated, but actively celebrated, where they were willing for their countries to be subsumed into the Western-dominated global market.

A system built on illusions can't keep reality in a headlock forever. Twenty years ago, fascist groups radicalised by US troops in the Holy Land smashed into the Twin Towers and baited Washington into a 30-year war. While the credit that was crunched in the 2008 financial collapse has largely been re-issued, the sense of shared riches in the 1990s has been replaced in the West by a deep feeling that something is broken. And US defeat in Iraq, and now Afghanistan, only confirms that sense. After all, can you think of a war that the US has won this century?

We already had signs that neoliberalism was crumbling, as authoritarian and nationalist capitalists have taken control of countries from India to Brazil, and even the former technocrats of market rule swung the state into action as the pandemic arrived.

But US defeat in Afghanistan is another sign that the neoliberal era is over, because it marks the death - for now - of that attempt to unite the world into a US-led market.

And it also tells us something about what will likely replace it. As openDemocracy's international security adviser, Paul Rogers, has pointed out, the Chinese government has much to gain. Earlier this month, the Taliban's political chief, Mullah Abdul Ghani Baradar, met with Beijing's foreign minister, Wang Yi. The tiny border between the two countries - the Wakhan Corridor - comes at the end of a finger between Tajikistan and Afghanistan, a legacy of 19th-century games between the Russian and British empires.

This finger, combined with an alliance with a Taliban government, would allow Chinese capital new trade routes into the Middle East and the West. If neoliberalism was about the power of American capital, then there's every chance that what comes next is increased Beijing hegemony, with its system of authoritarian capitalism dominating both East and West.

There is also every chance to resist.

But as ever, the people of Afghanistan will continue to be treated as roadkill on someone else's journey.

From openDemocracy

Leave a Comment

Recent Posts

The forensic clean up of the f ...

Much of the coverage centring the surge in Non Performing Loans (NPLs) ...

Hong Kong’s deadliest fire in ...

Hong Kong’s deadliest fire in decades left at least 44 people de ...

False document submission hurts genuine students’ ch ..

The Missing Ingredients for Peace in Palestine

Songs of Hyacinth Boats & Hands: Reading Conversatio ..

Executive Editor Julie Pace on why AP is standing fo ..