Essays

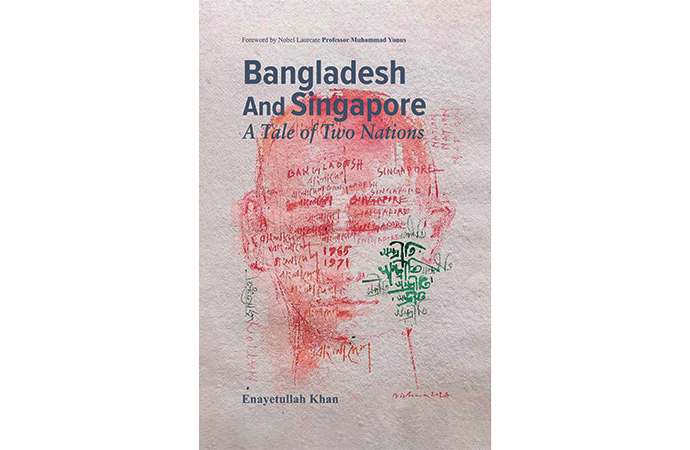

By Enayetullah Khan, Cosmos Books, 2024, 236 PAGES, BDT 1,000. Review by Asad Latif

Enayetullah Khan is a Bangladeshi entrepreneur who has built his Cosmos Group into a globalised national conglomerate. He is also a nature, heritage and ocean conservationist; a patron of the arts; and a media personality. He has visited Singapore regularly since the 1970s, and now divides his time between his home and host nations.

In this book, he takes a comparative look at the national strategies of Bangladesh and Singapore. In doing so, he brings into play a fine cosmopolitan sense of what makes each country distinctive and yet also what connects them internationally. The book is marked by an urbane feel for internationalist values that apply to decolonised nations as they make their way through the uncharted waters of global affairs.

Singapore became independent in 1965; Bangladesh in 1971. Their independence was in a sense a dual, two-stage, one. Singapore was ejected from an independent Malaysia which had won its own freedom from Britain in 1957. Bangladesh (the erstwhile East Pakistan) broke away from Pakistan 24 years after Pakistan, then a part of India, had achieved independence from British rule in 1947. If nothing else, the ruptures present in the historical provenance of Singapore and Bangladesh connect them intimately.

But there is much else as well. Nations have been called imagined communities, that is, they are brought into being by the active imagination of their citizens who decide to prize what unites them with fellow-citizens over what unites them with members of the same race or religion who live outside state borders.

Khan's comparative perspective narrates brilliantly how multi-racialism has created Singapore in an overwhelmingly ethnically-Chinese nation; and how the sense of being Bangladeshi has created a nation in which that country's overwhelming Bengali-Muslim majority has found space and peace with non-Muslim Bengalis, non-Bengali Muslims and those who are neither Bengali nor Muslim, such as members of certain hill tribes.

The book devotes a chapter to Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and Lee Kuan Yew, the founding fathers of their nations. Thankfully, there is no glorification involved here, just a cerebrally-calibrated look at how the two men managed to galvanise their peoples around a coherent national purpose.

That is fair enough. The importance of adopting this approach is apparent in the attacks on the iconicity of Mujib - who is known as Bangabandhu, or Friend of Bengal - following the street ouster of the despotic government led by his daughter, Sheikh Hasina. The hagiographic danger of centring nationalism on a single leader, no matter how singular he might have been, has been avoided in Singapore, where the political system continues unmolested a decade after Lee's passing.

What matter at least as much as individuals are institutions. Khan takes a penetrating look at the workings of two such national institutions: Bangladesh's Grameen Bank, and Singapore's Housing and Development Board (HDB). National development has to be concrete, tangible and tactile if it is to mean anything. Grameen Bank's ability to turn microfinancing into a viable instrument of national development earned its founder, Muhammad Yunus, the Nobel Prize, and has led to him helming the interim government of Bangladesh after the fall of the Hasina regime. Singapore's HDB - now the Housing Board - continues to underpin the national stability that it inaugurated under former National Development Minister Lim Kim San, who won the Magsaysay Prize (Asia's equivalent of the Nobel) for his literally nation-building efforts. To build public housing is a build a nation from below.

However, a roof over the familial head is not sufficient. There must be as well communication and conversation in the collective home called the nation. Those larger assets are provided by culture. Bangladesh's cultural riches are known to all who seek to understand Asia. Khan speaks of them in intimately personal terms and relates them to the way in which an intrinsically Singaporean culture has been formed out of the immigrant traditions of Chinese and Indians that melded with the culture of Malays and Eurasians.

The chapter on the two economies of Bangladesh and Singapore places their developmental trajectories firmly within the indigenous realities of two decolonised nations seeking survival and success. This chapter explores the way in which the two countries sought to find a formula that would avoid the extremes of laissez-faire capitalism and state-centric socialism in order to release the economic energies of their populations. Singapore's success in this regard is one that Bangladesh could choose to emulate on its own terms as it emerges as an economic player in South Asia.

Finally, Khan goes into cautionary mode in arguing that the fortunes of small countries such as Bangladesh and Singapore are tied to the vagaries of great-power relations. The rivalry between the United States and China augurs badly for both small nations, who cannot control the outcome but must face its consequences.

Yes. On the road to that ultimate denouement, Bangladesh and Singapore could come closer. Then, this book would have served its purpose.

The writer is the Principal Research Fellow of the Cosmos Foundation. He may be reached at epaaropaar@gmail.com

Leave a Comment

Recent Posts

Another stress-test for the wo ...

And just like that, the world economy has been thrown into turmoil onc ...

Turkish President Recep Tayyip ...

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan offered to mediate for a new ce ...

Bangladesh flags economic risks of prolonged Middle ..

Bangladesh seeks enhanced cooperation with Argentina

US trade deal discussed with BNP, Jamaat before sign ..

Road Transport and Bridges, Shipping, and Railways M ..