Global

A survivor's mother in West Bengal, with items belonging to her daughter who was gang-raped and murdered. | Picture courtesy of Priyanka Dubey.

Priyanka Dubey, an award-winning journalist, spent six years researching and documenting India's unreported rape cases for her new book, "No Nation For Women - Reporting On Rape From India, The World's Largest Democracy".

Released in India in December, the book is out in the UK and US as well, from 8 March, International Women's Day. It includes eye-opening, investigative reportage from India's hinterland, where national media, especially English language platforms, rarely set foot.

I recently spoke to Dubey by Skype, after her return from the serene hills of Uttrakhand in northern India, to her home in the country's capital of New Delhi. It was the first vacation she had taken since starting work on the book she says "was waiting to be written".

India is known as one of the world's most dangerous places for women - with estimates that a woman is raped in the country every fifteen minutes. But while reports of rape increased by 873% between 1971 and 2011, as many as 99% still go unreported.

It's true that the world knows the story of Jyoti Singh, the physiotherapy student who died after being brutally gang-raped on a New Delhi bus in 2012. Yet few people, including in India, have heard of the children Kavita and Ragini, in the city of Badaun, in the northern Uttar Pradesh state, who were raped, murdered, mutilated in 2014.

In her book Dubey describes with vivid detail how these children were left by their abusers "hanging from the mango tree - slowly swinging in the burning afternoon winds".

Another case is that of a 17-year-old girl from West Bengal, whose body was found in 2013 by a canal, half-naked and cut with deep blade marks. Dubey recalls in the book how the girl's mother said it was as if "someone had peeled her skin off like we peel onions at home".

No Nation for Women's thirteen chapters explore the patriarchal circumstances that have contributed to such extreme levels of sexual violence in the country. But it isn't these underexplored or brutal details that make this book groundbreaking.

Rather, it's how Dubey dismantles notions of rape as a singular, common experience. When we spoke, she explained that "rape is multi-layered in India and it manifests itself differently in various social, geographical and cultural situations".

She insisted: "To generalise rape in any way is to take the discourse backward".

Dubey's book documents 'corrective rapes' in the Bundelkhand region; girls burnt alive in the northern Madhya Pradesh state for resisting the advances of neighborhood men; 'political rapes' in the Tripura state, on the border with Bangladesh.

In West Bengal, "as women are being more educated and achieving an elevated standard of life, organised crimes against them is increasing". Dubey describes this violence as a reflection of the desire to "put a woman in her place".

Her reporting stands in stark contrast with that of India's mainstream media, whose overage of rape often lacks context and seems to have desensitised people towards it.

Unlike this coverage, Dubey also pays needed attention to relationships between rape and India's caste system, a 3,000-year-old hierarchical social system of Hinduism which divided communities into castes and their sub-castes, according to their professions.

The lower you were in this caste system, the more likely you were to be poor. Although India banned caste-based discrimination in 1950 soon after its independence from the UK, it remains significant, particularly in rural areas.

"In my experience of reporting, if you are lower caste woman in rural India, you are more likely to be raped", Dubey told me, powerfully describing how "women's bodies are used as a battleground to establish caste supremacy".

One of the cases in her book is that of four underage Dalit girls, from the lowest category in the caste system, who were abducted in 2014 just 500 meters from their home in Bhagana, in the northern Haryana state, and gang-raped by upper caste 'Jat' men.

One of the rape survivors' mother told Dubey that they came from a community of landless farmers on Jat fields, and "of course, the Jat owner thinks he has every right over the daughters and wives of his Dalit bonded labourer".

"There have been many cases", the woman continued, "when Jats enter the homes of Dalits on any given night and ask the man to step out, giving him such a task as watering the fields. Then they sleep with their women".

The question for justice for victims and survivors of sexual violence is another point where India's mainstream media usually loses interest.

While India established fast-track courts exclusively for such cases after the 2012 Delhi bus gang rape, it still had 133,000 cases pending last year.

Here, Dubey shows how caste-based privilege has enabled perpetrators to derail police investigations, describing a common strategy as trying "to make cases against them inconclusive so they can either get acquitted or drag on the case for decades".

She looks at how police, doctors and even magistrates have refused to register rape cases; manipulated witnesses into being 'hostile' towards survivors; tampered with forensic evidence; and threatened women into withdrawing their cases.

The result is a total breakdown of law and order and "the death of justice", Dubey writes, "the final defeat of democracy, the constitution and the kindness of the human spirit".

On top of the violence itself and the denial of justice, stigma looms large over survivors. The mother of a three-year-old girl who was raped in East Delhi confided in Dubey that neighbours branded the girl as 'greedy' because her rapists had lured her with sweets.

For every reported rape case, says No Nation For Women, dozens of others go unreported because of fear and shame. "Rape is the only crime in India for which the victim is blamed", Dubey writes. "Everyone - right from the family, friends, to the police - views the victim with doubt. Her testimony is dismissed... [with] random questions on her character".

The book paints a picture so bleak that hope for marginalised women in India seems like a distant and even ridiculous dream. Yet, it is this very darkness that is its strength.

Dubey has ditched the noise surrounding women's empowerment and gender sensitivity in elite India. Instead, she has brought attention to the "parallel universe" of gruesome crime and injustice that has gone callously unacknowledged by the country.

How? By analysing heaps of legal paperwork, police files and post-mortem reports. Most importantly, Dubey listened to rape survivors and their families, for hours on end, to record the entirety of their truths, dreams, ambitions, loves and harrowing losses.

With the exception of the feminist writer and publisher Urvashi Bhutalia's work, documenting violence against women during the Partition, Dubey said she "couldn't find any long-form non-fiction on ground reportage of rape in India".

She called her book one that "was waiting to be written. And I really wanted to write it". Though doing so wasn't easy, and it took a significant toll on Dubey.

She couldn't always foresee danger when reporting from deeply patriarchal areas, for instance. In the very first chapter of her book, Dubey discloses that she was groped in the night by a group of men on a train when traveling for a story.

Working on this book was also "a soul-bruising experience", she told me, recalling how she'd listen to tapes of survivors' testimonies over and over again. "You don't understand all the wounds those stories leave on you. You can never fully recover".

A frugal lifestyle to self-finance the reporting in her book also impacte Dubey's health. She struggled to make time for friends in her personal life while her family, in her conservative hometown of Bhopal, had long disapproved of her profession.

"They thought it was disrespectful and unsafe", Dubey said. "Where I come from, women did not become journalists. At least not at the time I was starting out".

Against these odds, what kept Dubey, who now reports on gender issues for the BBC, going? "When people have trusted me enough to share their most intimate pain with me, I have to tell their story", she told me. "My first accountability lies with my story. Always".

Payal Mohta is a freelance journalist based in Mumbai, India. She covers stories relating to gender, identity and communities. Her work has been published in The Guardian, Vice Media, UK and various other magazines and newspapers. www.payalmohta.com

Leave a Comment

Recent Posts

Destination Election

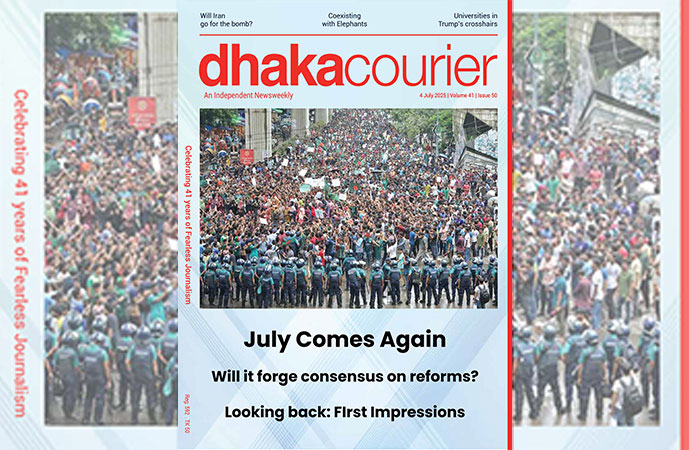

The first anniversary of last year’s July Uprising, an epochal e ...

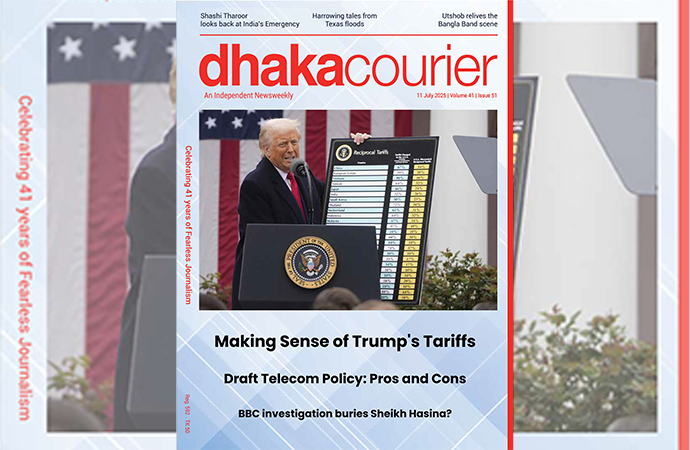

US President Donald Trump sign ...

US President Donald Trump signed an executive order Wednesday (Aug. 6) ...

Chief Adviser Muhammad Yunus wrote to the Election C ..

Next year’s election to mark major test for post-Has ..

Dutch envoy lauds Prof Yunus for steering Bangladesh ..

When teachers learn from their own teaching: My case ..