Essays

The opening line of T.S. Eliot's seminal poem The Waste Land "April is the cruelest month" echoed in my mind once again. In Eliot's masterpiece, April symbolizes a time of painful rebirth, unfulfilled hope, and existential despair. Strangely enough, in Bangladesh's current political context, the month of April seems to be acquiring a similarly bleak and bitter symbolism.

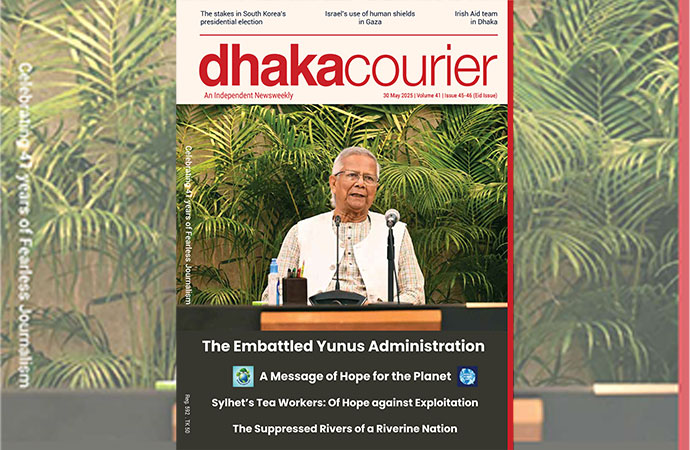

On June 6, the Chief Adviser to the interim government formally announced that the next general election would be held in the first half of April 2026. Though he had previously indicated that the election could be held anytime between December 2025 and June 2026, this was the first time a concrete timeline was offered. "After reviewing the ongoing activities related to justice, reform, and the election process," he said, "I hereby announce to the nation that the next national election will be held in the first half of April 2026. Based on this announcement, the Election Commission will later publish a detailed roadmap."

The reaction from political quarters has been swift and polarized. The BNP and its allies have termed the declaration politically inappropriate and unilateral. Their demand had been consistent: a free, fair, and inclusive election should be held by December 2025. They argue that April is an unsuitable time for elections due to public examinations, extreme weather conditions, and the overlap with the month of Ramadan, which complicates election campaigning and mobilization.

While BNP and its allies pushed for a December poll, the Jamaat-e-Islami and the National Citizen Party (NCP) advocated for an election after ongoing judicial and institutional reforms-pointing squarely at April. The Chief of Army Staff had also reportedly favored a December election. Yet, the Chief Adviser has tilted toward the Jamaat-NCP camp, ignoring not only the military's advice but also the consensus among the country's major political forces.

This decision has raised questions about the neutrality of the Chief Adviser. He was appointed with widespread public support, and his role was presumed to be nonpartisan. But his apparent sympathy for the NCP and his tolerance of Jamaat's presence in political dialogue has been viewed by many as troubling. Critics argue that this decision undermines both the perception and reality of his neutrality.

By unilaterally fixing the election for April, the Chief Adviser seems to have ignored public sentiment and political consensus. Political analysts suggest this reflects a rigid and possibly arrogant stance. Moreover, the announcement makes it clear that he does not intend to accommodate the BNP's demands and, perhaps more significantly, that he is asserting his authority over the military establishment by dismissing its timeline preference. The fact that the NCP and Jamaat welcomed the announcement only strengthens the perception that the decision was made with their interests in mind.

The BNP has responded by pointing out the unsuitability of April due to the aforementioned factors. They also fear that the April timeline is a strategic move by the interim government to later postpone the election, citing weather and exams as reasons. Such suspicion is not unfounded, given the long history of political delay tactics in Bangladesh.

What remains unclear is why the government is dragging its feet on fixing an election date. Initially, the Chief Adviser mentioned a window between December and June. But why not December, January, or February? Why specifically in April? These are legitimate questions, especially given the slow pace of progress on judicial and institutional reforms over the past ten months.

Various commissions have submitted reform proposals. There is even some consensus among political parties on a minimal reform agenda. But we have yet to see a concrete roadmap or substantial democratic transformation. Judicial processes, by their very nature, are lengthy. If reforms and trials can't be completed by December, they are equally unlikely to conclude by April. So again, why was April chosen?

The interim government came to power with a threefold mandate: to carry out reforms, ensure justice, and conduct elections. In his latest speech, the Chief Adviser expressed confidence that the government would reach an "acceptable stage" on reforms and justice by April. But what defines that "acceptable stage"? If reforms are broadly supported and no political party opposes justice, why can't meaningful progress be made by December? Why is the delay until April?

Particularly on the matter of prosecuting war crimes and crimes against humanity, a collective responsibility toward those martyred in the July uprising-the Chief Adviser mentioned that there would be "visible progress." But what exactly does "visible progress" mean? So far, we've seen little progress on institutional reforms, and the judicial process remains bogged down. One need only recall the example of former state minister Lutfozzaman Babar. Despite being sentenced to death, he remained in prison for 17 years and the verdict was never executed due to lengthy legal procedures.

The government surely knows that neither judicial nor reform processes can be completed by April. So again, the question: why the insistence on April? The real issue at hand is ensuring a credible election where people can exercise their right to vote-something they've been denied in the last three elections. Electoral reform is the most critical reform of all, yet the government seems disinterested in prioritizing it. This is why people doubt whether the government is even sincere about holding elections at all.

With nearly a year to go, anything could happen. Some groups are actively working to destabilize the country, and regional actors, particularly, India is waging continuous propaganda campaigns against the government. The NCP's agenda includes implementing the July Declaration, holding a Constituent Assembly election, and a local government election. If these goals can be achieved by July 2025, why push the election back to April 2026?

Many suspect that the delay is strategic, allowing the interim government to prolong its stay in power under the guise of reforms and justice. Meanwhile, the BNP is being cornered, portrayed as standing in the way of progress and indirectly equated with destabilization efforts. Propaganda by the NCP and its media allies against the BNP appears coordinated. This benefits the Jamaat-NCP axis, allowing them to build political capital while discrediting the BNP.

In this situation, what should the BNP do? They continue to call for an election by December-though pragmatically, this might stretch to February. Their strategy should be to stay calm, measured, and politically focused. Any move toward confrontation would only play into the government's hands, providing the perfect pretext for further delay and allowing Jamaat-NCP to claim the moral high ground.

Perhaps, this is the government's real game: to provoke the BNP into conflict, thereby legitimizing an extended interim regime and allowing fringe actors to gain political momentum. But is this sustainable in the current national context?

Ultimately, the question is whether the government is committed to a genuine democratic transition. If so, the best path forward is to immediately open inclusive dialogue with all political stakeholders and aim for an election by December. Otherwise, Eliot's "cruelest month" will cease to be just a poetic metaphor. It will become a political reality-one with consequences the nation may not be able to bear.

Ahmed Swapan Mahmud is a poet and human rights activist. He can be reached at ahmed.swapan@gmail.com

Leave a Comment

Recent Posts

Cosmos Group VP Nahar Khan hos ...

A visiting delegation from Meta, the parent company of Facebook, Insta ...

Break the gloom, build a bette ...

Emphasising the transformative power of social business and its strong ...

‘Mobocracy’ must not prevail

The US Supreme Court allowed the Trump administratio ..

Germany dependable partner in our development journe ..

15th edition of Social Business Day: Prof Yunus to j ..